Kyle Shanahan unveiled a cool new play Sunday. Should he have?

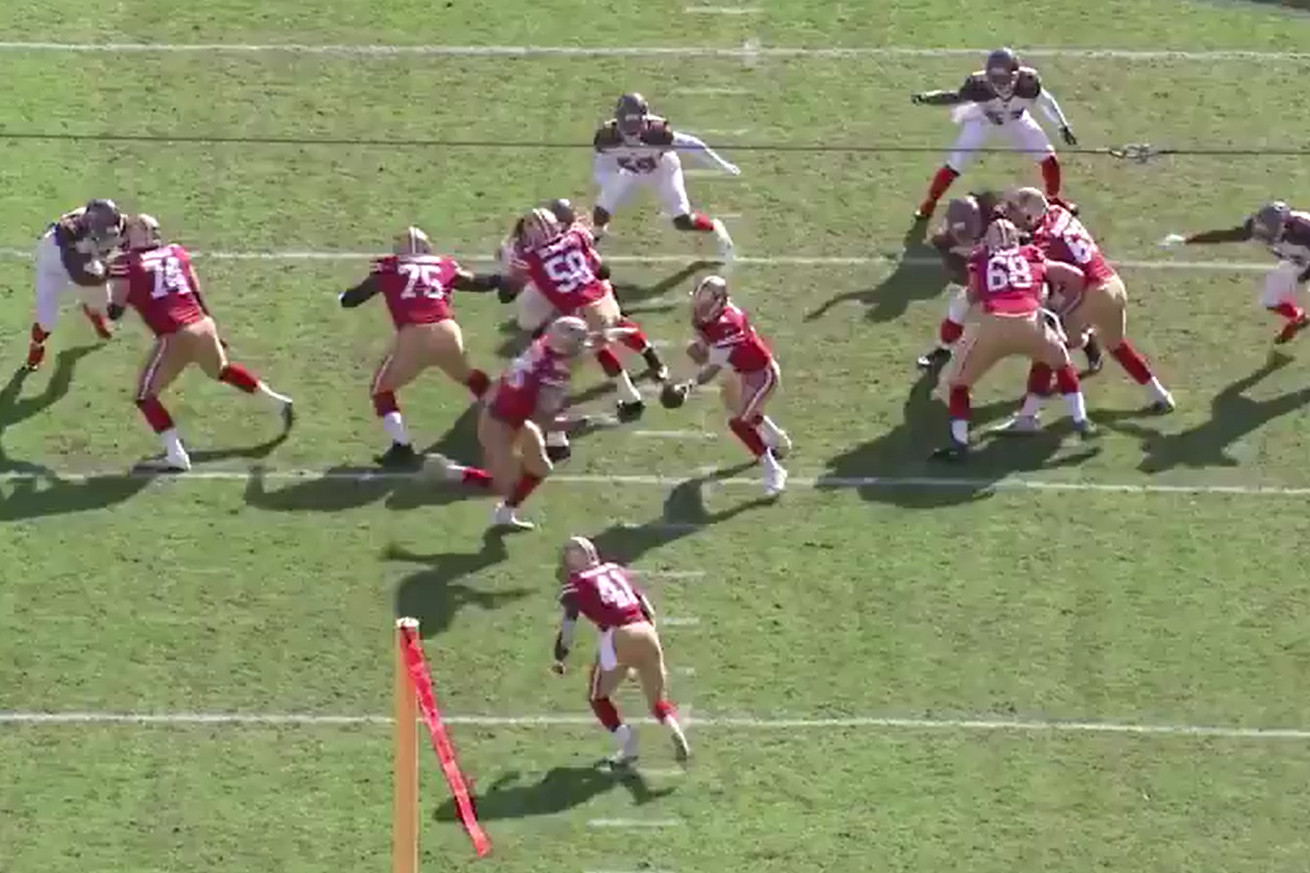

With 12:54 left in the 2nd quarter against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, it was 1st and 10 for the Niners at their own 32. George Kittle, Richie James Jr., and Kendrick Bourne lined up in a bunch, very tight to the right side of the offensive line.

Kittle motioned into the left slot and set up. Then he came back in motion to his right, and took a quick handoff from Mullens right after the snap. James Jr. and Bourne joined forces to block CB Javien Elliott (#35), driving him back nine yards as Kittle ran around the right end, outracing LB Adarius Taylor (53) for a ten yard gain.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13590627/Kittle_sweep_vs_TB_11_26_18.gif)

This was a brilliant innovation. There are lots of “football 101” articles about jet sweeps and end-arounds, and the difference between jet, fly, and regular sweeps; these are often cranky about terminology. I couldn’t find a single one of these that mentioned the possibility of a tight end taking the handoff, instead of a wide receiver or wing back.

There’s a fundamental difference running the tight end in motion instead of a wide receiver. With a wideout, the expectation is that pre-snap motion gets them to full speed at the point of the hand-off, and they’ll be able to outrun any linemen (who are starting from zero) regardless of how the offensive line blocks. At the same time, the receiver’s motion will naturally draw the defense’s attention, which makes the motion useful as a decoy, to fake the WR hand-off and give it to the running back going in the opposite direction.

Tight ends (and full backs) often go in motion behind the OL pre-snap and just after the snap, too. But the meaning is very different. Defenses will expect them to be perimeter blocking for the running back on a sweep, or alternatively blocking the backside DE on a “wham” or “split-zone” play.

So while Kittle’s motion is similar to a WR’s in a typical jet sweep, the read for the defense is completely different. I think it’s also safe to assume that a cornerback looking at Richie James Jr. and Kendrick Bourne just right of the line doesn’t generally expect them to double-team block him.

This play made a lot of sense, for both good and bad reasons. It sets up similar additional plays in Shanahan’s offense and goes somewhere completely unpredictable. Kittle is a gifted runner. As the announcers on Sunday’s game pointed out, he was (at the time) second in the NFL for yards after catch, after only Saquon Barkley, and the only tight end in the top nine.

At the same time, with Pierre Garçon and Marquise Goodwin out, Kittle was the team’s best and most predictable receiving target, so this was a new way to get him the ball. I’m surprised defenses don’t double-team or bracket him on every offensive down.

But this raises a question: should Shanahan be revealing cool new plays deep into a lost season? Or should he save these for more important games next year?

Without getting into the whole “tanking” debate, I don’t think anyone complains about a coach keeping a key play (such as “Philly Special”) for a crucial moment (like, say, 4th and goal in the Super Bowl against the Evil Empire).

Fooch made a good counter-argument, though, when we discussed this.

“You put that on film, teams next year might feel like they need to pay closer attention, maybe it opens up a run lane from the direction Kittle started at.”

Ultimately, it boils down to whether this is a trick play or a constraint play. A trick play succeeds only by the element of surprise; if the defense sees it coming, they can easily blow it up. Obviously that is one you want to keep secret for the crucial moment.

Nick Foles was a tight end in high school (as well as a basketball player) and has good hands. He is slower than most good offensive linemen, though (5.14 in the 40 yard dash), and he was very unlikely to have gotten open if a linebacker thought there was any reason to cover him coming out of the backfield.

A constraint play, though, is more like a jiu-jitsu move. It takes the power of the defense’s motion and uses it against them. When the D starts cheating in the direction of a play, a constraint play typically starts out looking like that play, then shifts to the opposite direction — which the defense is running away from.

To pick a couple of recent examples, the wildcat was a trick play — well, trick formation, I suppose — while the read-option is a constraint play that punishes over-commitment by the defense — and keeps them guessing.

Sometimes just making a defender hesitate for a second, because they don’t know which way you are going, is all you need to spring a big play.

This tight end “jet” sweep looks more like a constraint play to me. What do you think?